Three capable men dominated and defined English painting in the high period of the Hanoverian kings. These were Thomas Gainsborough, Joseph Wright of Derby, and Joshua Reynolds, later knighted by George III.

Gainsborough was the pleasing painter to the nouveau riche, remembered best today for his gauzy, pastoral paintings of figures like Mr and Mrs Andrews. Sniffing at London society from his comfortable workshop in Bath, he painted the upper class and their families with an unceasing industry. Signs of this you can see in two paintings a few rooms apart in the National Gallery’s collection – although the portraits are gorgeous and done with the masterly care that made him famous, the backgrounds are essentially identical, anticipatory in a perverse way of the scroll-mechanism backgrounds of late 20th century department store family portraiture.

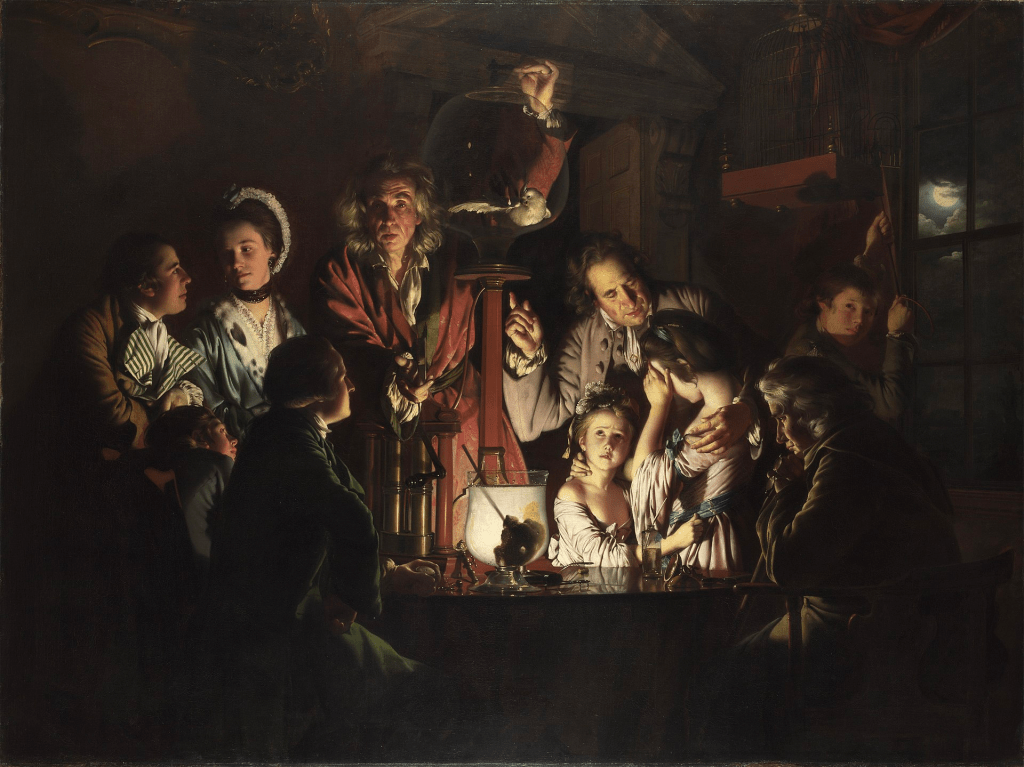

Reynolds was London’s favorite, a man who hobnobbed with leading lights of the age like Adam Smith, Dr Samuel Johnson, and James Boswell. Steady, focused compositions of courtly figures were his watchword. Joseph Wright, remembered with the strange moniker “of Derby,” innovated in the depiction of science. Whether in clinics or cozy hearths, Wright’s learned men exhibited the newfound principles of physics and anatomy in exquisite detail.

The acme of their common achievements came in 1768 when Reynolds and his circle in London successfully petitioned the King for a charter to create the Royal Society. Kindly, Reynolds invited Gainsborough to become a founding member as well, although he was slighted by being out of Zoffany’s depiction of the initial class.

When the three of them passed on in the last decade of the eighteenth century, they left in their place a vacuum which would come to be filled by two new competing forces – the neoclassicism of the Americans and the romanticism of their young fellow countrymen.

American painting emerges from the Revolutionary period with a surprising degree of strength. Shedding its “naive” period, a style whose formal qualities gave it a look that remains odd today, the greatest of the new generation of painters in the early republic sang the new nation from bottom to top. Gilbert Stuart and John Trumbull painted the founding fathers in warm reds surrounded by fascia and other appurtenances of Roman descent, a motivic language they could speak to other Atlantic-world court painters in the age of revolutions, certainly to men no less than David in France.

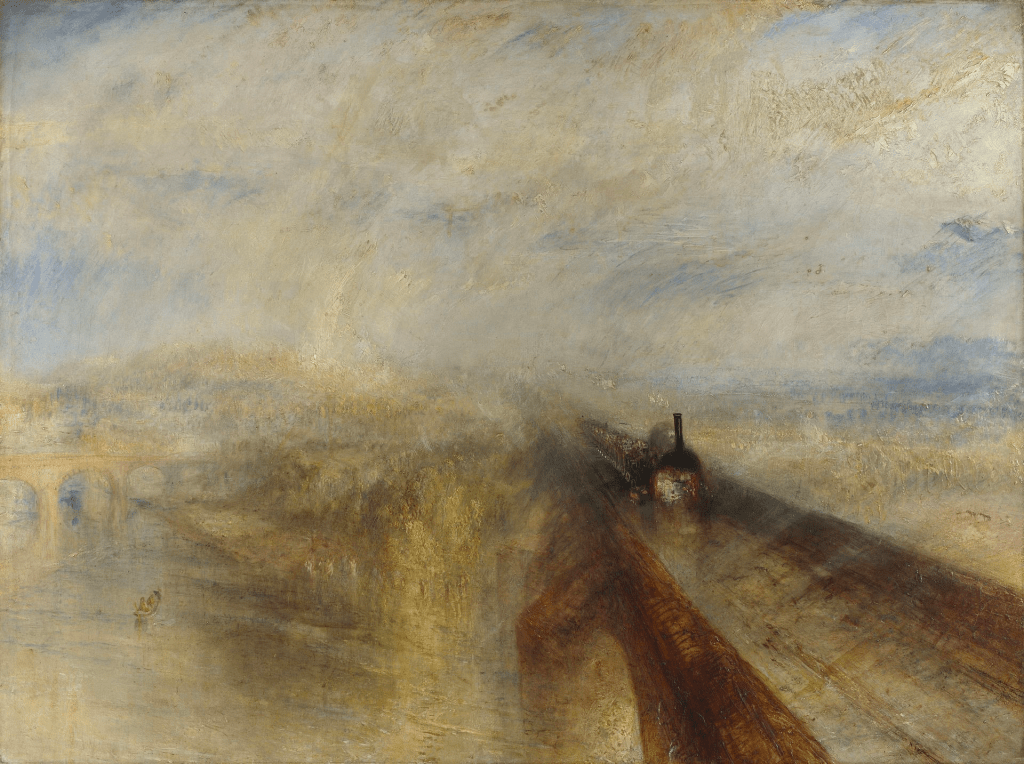

By contrast the new Englishmen took their cues from the continent, where the nation’s focus was trained for the better part of three decades after 1793. In gloomy Brandenburg, Goethe and Schiller and Friedrich put together brooding, agony-filled works of art in a style called the Romantic, and painters like John Constable and JMW Turner took to this with ferocity. Turner is the exemplar, something like a prophet of the modern, his swirling seascapes breaking the geometry of reality to emphasize the inescapable tempest of nascent industrial life. Pat scenes of ships-o’-the-line in combat off Brest became in his hands transcendental tableaux; a railroad crossing the Thames opens a portal to the future in Dionysian mystery, bursting the door open wide for Wassily Kandinsky and Georges Braque, whose hearts we can understand as our own.

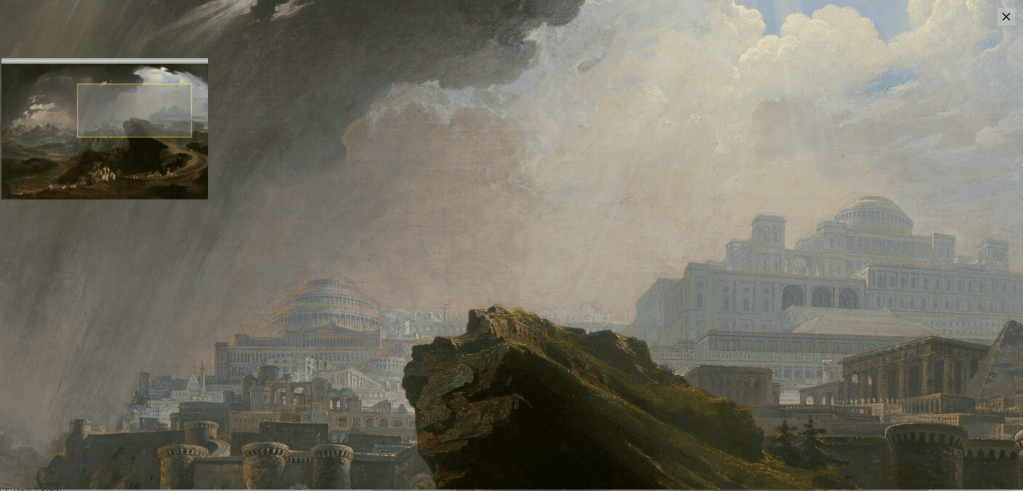

An evolutionary missing link is presented by the work of John Martin, who was born after the death of Sir Reynolds. His painting below, Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still Upon Gibeon, struck me when I saw it while younger and still does so today. If we need to give it labels, it mixes history and landscape painting on an epic scale – depictions of triumph are old as dirt, but the panache Martin invests in his 5’x7′ canvas (which is huge!) sets this apart.

Lightning and hail strike the fleeing Canaanites while epic ziggurats look on smooth and petrified. The sun and moon spill unnatural amounts of light in their own corners of the painting, leaving the rest of the scene shadowed, which imparts to the viewer the feeling of watching a show during an eclipse.

Martin’s biblical architecture wouldn’t feel out of place in the megalomania of Fritz Lang, a comparison of artists perhaps not as far off as it might seem – Martin was disdained even in his own time for an overweening sentimentality, a dedication to a sort of Sir Walter Scott-esque arc of history which others around him found merely jejune.

I like Martin, and I like Gainsborough and all the rest of the people who made their living putting oil to canvas. We miss their scale of interpretation and their care for the details. David Lynch said that he got into filmmaking in order to make paintings that moved, but we’re not making many more Lynches these days.